Postcard from Europe: It’s not just British farmers who feel under attack.

This article originally appeared in Farmers Weekly

Farmers’ faith in government may be at a historic low, but it’s no different on the Continent, where trade deals can still impact Britain.

Another tractor motorcade will roll into Parliament Square next week over national food security, interrupting almost two months of calm during spring sowing season.

Yet with Continental-style sun bearing down on us, it’s worth comparing our levels of farming uproar with our European neighbours, particularly the usually volatile French. Rampaging French farmers spraying government buildings with manure happened as recently as January and so it’s not just a cliché. But without inheritance tax changes, what are they so angry about?

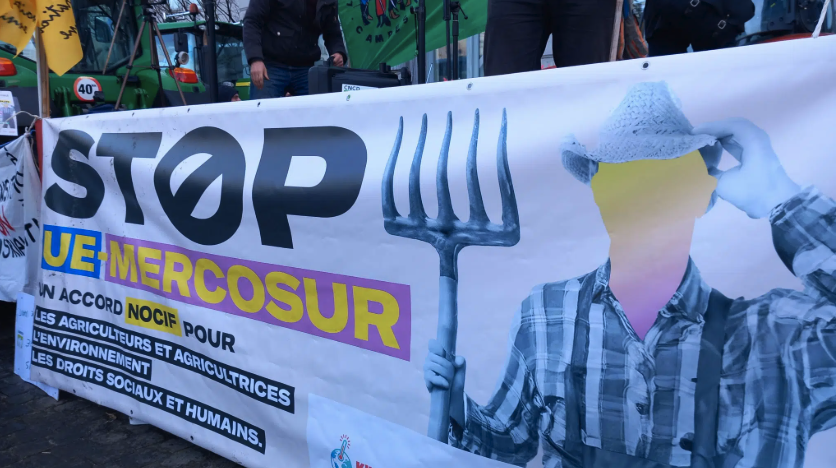

Post-Brexit, the EU could plough on full steam ahead with its plans for deeper integration without the pesky Brits throwing a spanner in the works. That was the theory, but in reality Europe is on the cusp of a major split over a free trade deal with the five South American countries making up the ‘Mercosur’ bloc of Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay and Bolivia. A deal that’s been agreed in principle but still has a long way to go before the effects are felt.

The furore has been 25 years in the making as the EU-Mercosur agreement, after countless setbacks and delays, was finally signed just before Christmas by European Commission President Von der Leyen.

The deal would gradually remove tariffs on over 90 per cent of EU goods exported to Mercosur in return for preferential EU market access for hundreds of thousands of tonnes of South American beef and poultry. It will be the biggest trade deal on the planet. The perfect antidote for Europe to ‘Trump-proof’ itself against an unreliable US.

But Von der Leyen’s signing off is just the first step in the EU’s ‘sausage-machine’ making process. The deal must then be ratified by the European Parliament (a simple majority of 361 MEPs) plus the Council of the EU (at least 15 member states, representing at least 65% of the EU population).

This is where things get tricky, as France could torpedo the whole deal. Yet farmers from all over Europe were on the march for the same reason British farmers objected to the post-Brexit deals with Australia and New Zealand, or any future deal with the US. It’s the worry of being undercut by cheaper meat produced to a lower standard. Suddenly phrases like ‘chlorinated chicken’ and ‘hormone induced beef’ are now mainstays in the EU agri press.

And with Starmer’s ‘Brexit Reset summit’ happening on May 19th, some of these products could wash up on our shores, once the current ban on EU meat is lifted. Talk of ‘dynamic alignment’ means we’ll follow EU standards to improve our own deal with Europe to kickstart economic growth.

“Ye have failed Irish farmers” barked far left Irish MEP Ming Flanagan at EU trade chief Maroš Šefčovič while trying to justify the deal in the Parliament. In an unprecedented turn of events, left-wing politicians and environmental NGOs have joined forces with the massive EU agri super-lobby Copa-Cogeca (of which the NFU is still a member) to denounce the deal.

Climate groups are furious at the EU having a trading relationship with a country like Brazil, guilty of desecrating the Amazon rainforest. And these forces have combined with the surge in support for far-right politicians standing in solidarity with European farmers against the EU which wants to ‘destroy our way of life’.

Foreseeing this ‘protectionist’ opposition, the European Commission cobbled together a €1bn fund in case the deal has any damaging effects on national markets. Paltry, considering the EU’s GDP of over €17tn, but still lightyears ahead of what Truss and Eustice negotiated for us with our deals down under. Yet Green MEP Vicent Marzà argues that the sheer existence of this fund suggests that the Commission predicts farmers will be undercut by their South American rivals.

To quell concerns about lower standards the EU beefed up its certification regime by having inspectors on the ground in South America and a strict list of which producers can ship products to Europe. Europe’s concerns have meant the deal will only allow up to 99,000 tonnes of shipments to Europe. Hardly a new dawn, given that Brazil alone exports 200,000 tonnes of meat products a year to China a year.

But it’s not just EU-Mercosur that’s roiling our continental cousins, the CAP has changed too. Since the start of 2023, the EU brought in eco-schemes just like our own ELMs. In fact, Defra were open in showing European agri attachés how it’s done. But at least with ELMs, we knew that changes were coming post-Brexit. As a farmer in Europe, how ready would you have been for ‘conditionalities’ attached to your subsidy money, due to a ‘European Green Deal’ that you’d never heard of?

Individual decisions across different countries matter as well and it’s not just Brussels to blame for protests. In the Netherlands, it was compulsory land sales to cut the nation’s nitrogen levels. Germany cut their subsidies for diesel tractor fuel. France imposes the highest standards on its farmers, especially on pesticides, while importing food from Italy that doesn’t have to follow suit.

Geopolitical and economic factors have taken their toll. Poland bore the brunt of the EU’s decision to remove tariffs on Ukrainian grain exports to help keep their wartime economy afloat. Most of the grain ended up in Poland, pushing down prices and hurting local producers. And Europe still has a ‘wine crisis’, with overproduction and falling consumption year on year.

European farmers are on the frontline of climate change and Spain and Italy didn’t provide enough emergency relief for farmers hit by drought (nor did the EU).

Despite these causes being quite relatable to Brits, it’s the narrative that’s still the same on both sides of the Channel. ‘Bureaucratic elites don’t understand what we’re going through’, ‘they want to change our way of life’, its ‘eco-lunacy’. It’s just a different culture of burning haystacks, tearing down statues and spraying police with milk directly from a cow’s udder.

Just before Christmas, Von der Leyen flew over to Montevideo and stood alongside four of the Mercosur premiers for a photoshoot that stuck in the craw of the Europeans passionate about their land and its produce. She wouldn’t have gone all the way over there if she thought she’d fail at ramming it through the EU’s law-making labyrinth. Yet like Starmer, she faces the same dilemma of economic growth versus the ire of farmers.